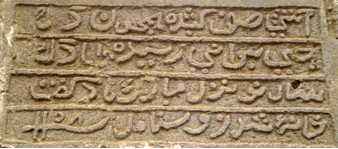

The original draft of article below, The Mithraic Mysteries, was originally written by the late Franz Cumont (1868-1947), with the version below edited and updated by Shapour Suren-Pahlav, host of the CAIS website.

Kindly note that the pictures/illustrations and accompanying descriptions of these do not appear in the original posting of Suren-Pahlav’s article in CAIS.

===========================================================

Most of the research into Mithraism, a religion with many parallels to Christianity, comes from two writers, Cumont and Ulansey with a variety of other writers input. Some Similarities Between Mithraism and Christianity are:

- Virgin birth

- Twelve followers

- Killing and resurrection

- Miracles

- Birthdate on December 25

- Morality

- Mankind’s savior

- Known as the Light of the world

Have you ever wondered why December 25th was chosen to celebrate the birth of Christ? If the accounts in the Bible are correct, the time of Jesus birth would have been closer to mid-summer, for this is when shepherds would have been “tending their flocks in the field” and the new lambs were born. Strange enough there is an ancient pagan religion, Mithraism, which dates back over 2,800 years that also celebrated the birth of their “savior” on that date. Many elements in the story of Jesus’ life and birth are either coincidental or borrowings from earlier and contemporary pagan religions. The most obviously similar of these is Mithraism. Roman Mithraism was a mystery religion with sacrifice and initiation. Like other mystery cults, there’s little recorded literary evidence.

![-Mithraeum Rome San Clemente]()

The Mithraeum located under Rome’s Basilica of San Clemente (Source: Public Domain).

What we know comes mainly from Christian detractors and archaeological evidence from Mithraic temples, inscriptions, and artistic representations of the god and other aspects of the cult. In an EAWC (Exploring Ancient World Cultures) essay entitled Mithraism, Alison Griffith explains Cumont’s theory of a Zoroastrian origin for the Roman Mithraist religion. While this theory is disputed, there was a Mitra in the Hindu pantheon and a minor deity named Mithra among the Persians as well. Cumont came to believe the religion spread westward from Eastern Roman provinces. However, as Griffith explains, there is little evidence of a Zoroastrian Mithra cult and most evidence for Mithraic worship comes from the western portion of the empire from which Cumont correctly deduced that:

“Mithraism was most popular among legionaries (of all ranks), and the members of the more marginal social groups who were not Roman citizens: freedmen, slaves, and merchants from various provinces….”

No women were allowed.

The Dawning of the Age of Aries

Ulansey says the main problem with basing Mithraism on a Zoroastrian cult is that there is no evidence that the Zoroastrians’ Mithra practiced bull killing, the central aspect of Roman Mithraic iconography. An image of Mithras killing the bull holds pride of place in each mithraeum (cave-like temple for the worship of Mithras). Ulansey believes the images of Mithras slaying the bull are actually astronomical star maps. In support of this he points out that all the figures represented in the iconography have a place in the constellations (Taurus, Canis Minor, Hydra, Corvus, and Scorpio). He says that the other iconography and even the initiation ceremonies are consistently astronomical. Mithras’ place as bull-slayer has cosmological significance because, if Ulansey is right, Mithraists attribute to their god the ability to shift the equinox from the constellation of Taurus to Aries: His killing of the bull symbolizes his supreme power: namely, the power to move the entire universe, which he had demonstrated by shifting the cosmic sphere in such a way that the spring equinox had moved out of Taurus the Bull.

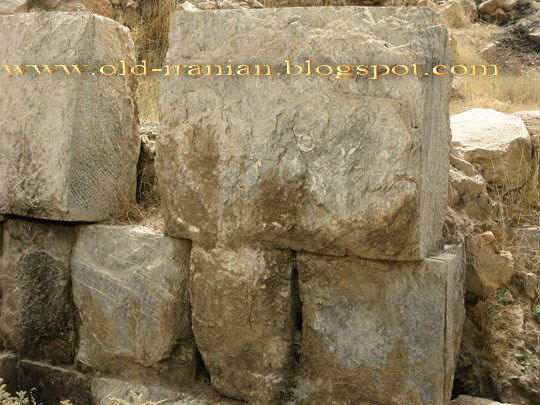

![-Column with Bull Motif at Persepolis]()

Column from Persepolis, capital of the Achaemenid Empire, with Double-Bull motif (Source: Based on photo by Luis Argerich for Public Domain).

For more research see:

- Professor Roger Beck: Mithraism

- Hinnells, John R., Studies in Mithraism: Papers associated with the Mithraic Panel organized on the occasion of the XVIth Congress of the International Association for the History of Religions.

- Hinnells, John R., Persian Mythology, Hamlyn, 1988.

- Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider Reviewed by Helen F. North. Twenty papers from the fourth international Mithraic congress held in Rome in 1990.

- Mithraism: A Historical Introduction

For over three hundred years the rulers of the Roman Empire worshipped the god Mithras. Known throughout Europe and Asia by the names Mithra, Mitra, Meitros, Mihr, Mehr, and Meher, the veneration of this god began around 3000 BCE in Persia, which was moved west and became imbedded with Babylonian doctrines. There is mention of Mithra or Mitra (et al) before 2800 BCE, but only as a minor diety and without much information. It appears to be after 2800 BCE when Mithra is transformed and starts to play a major role among the gods. The faith spread east through India to China, and reached west throughout the entire length of the Roman frontier; from Scotland to the Sahara Desert, and from Spain to the Black Sea. Sites of Mithraic worship have been found in Britain, Italy, Romania, Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Turkey, Persia, Armenia, Syria, Israel, and North Africa. In Rome, more than a hundred inscriptions dedicated to Mithra have been found, in addition to 75 sculpture fragments, and a series of Mithraic temples situated in all parts of the city. One of the largest Mithraic temples built in Italy now lies under the present site of the Church of St. Clemente, near the Colosseum in Rome. The widespread popularity and appeal of Mithraism as the final and most refined form of pre-Christian paganism was discussed by the Greek historian Herodotus, the Greek biographer Plutarch, the neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry, the Gnostic heretic Origen, and St. Jerome the church Father. Mithraism was quite often noted by many historians for its many astonishing similarities to Christianity. The faithful referred to Mithra as “the Light of the World”, symbol of truth, justice, and loyalty. He was mediator between heaven and earth and was a member of a Holy Trinity. According to Persian mythology, Mithras was born of a virgin given the title ‘Mother of God’.

![]()

Entrance to the Temple of Hatra in Iraq, possibly dedicated to Mithras (Source: Public Domain).

The god remained celibate throughout his life, and valued self-control, renunciation and resistance to sensuality among his worshippers. Mithras represented a system of ethics in which brotherhood was encouraged in order to unify against the forces of evil. The worshippers of Mithras held strong beliefs in a celestial heaven and an infernal hell. They believed that the benevolent powers of the god would sympathize with their suffering and grant them the final justice of immortality and eternal salvation in the world to come. They looked forward to a final day of Judgment in which the dead would resurrect, and to a final conflict that would destroy the existing order of all things to bring about the triumph of light over darkness.

Purification through a ritualistic baptism was required of the faithful, who also took part in a ceremony in which they drank wine and ate bread to symbolize the body and blood of the god. Sundays were held sacred, and the birth of the god was celebrated annually on December the 25th. After the earthly mission of this god had been accomplished, he took part in a Last Supper with his companions before ascending to heaven, to forever protect the faithful from above.

However, it would be a vast oversimplification to suggest that Mithraism was the single forerunner of early Christianity. Aside from Christ and Mithras, there were plenty of other deities (such as Osiris, Tammuz, Adonis, Balder, Attis, and Dionysus) said to have died and resurrected. Many classical heroic figures, such as Hercules, Perseus, and Theseus, were said to have been born through the union of a virgin mother and divine father. Virtually every pagan religious practice and festivity that couldn’t be suppressed or driven underground was eventually incorporated into the rites of Christianity as it spread across Europe and throughout the world.

The Persian Origins of Mithraism

In order to fully understand the religion of Mithraism it is necessary to look to its foundation in Persia, where originally a multitude of gods were worshipped. Amongst them were Ahura-Mazda, god of the skies, and Ahriman, god of darkness. In the seventeen or eighteen century B.C.E., a vast reformation of the Persian pantheon was undertaken by Zarathustra (known in Greek as Zoroaster), a prophet from the East of Iranian World, probably Bactria. The stature of Ahura-Mazda was elevated to that of supreme god of goodness, whereas the god Ahriman became the ultimate embodiment of evil. In the same way that Ahkenaton, Heliogabalus, and Mohammed later initiated henotheistic cults from the worship of their respective deities, Zarathustra created a henotheistic dualism with the gods Ahura-Mazda and Ahriman.

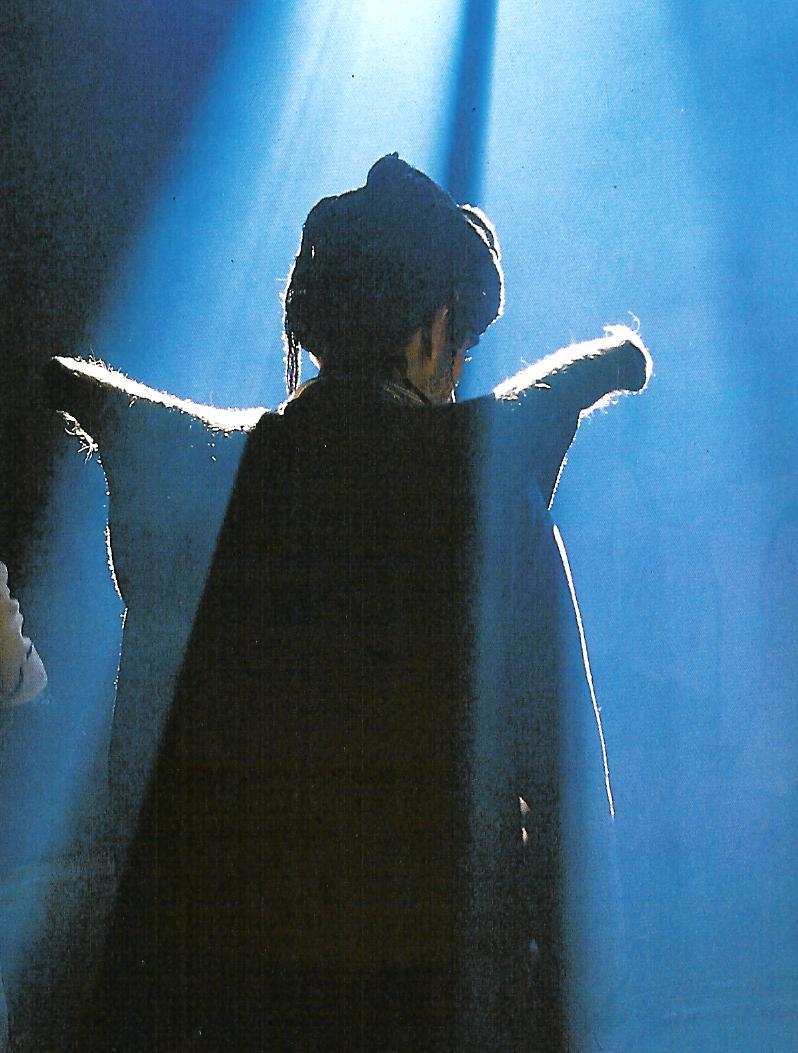

![kurd-engaged-in-worship-of-mithras]()

Kurdish man engaged in the worship of Mithras in a Pir’s (mystical leader/master) sanctuary which acts as a Mithraic temple (Source: Kasraian & Arshi, 1993, Plate 80). Note how he stands below an opening allowing for the “shining of the light”, almost exactly as seen with the statue in Ostia, Italy. These particular Kurds are said to pay homage to Mithras three times a day.

As a result of the Babylonian captivity of the Jews (597 B.C.E.) and their later emancipation by Cyrus the Great of Persia (538 B.C.E.), Zoroastrian dualism was to influence the Jewish belief in the existence of Ha-Shatan, the Adversary of the god YHVH, and later permit the evolution of the Christian Satan-Jehovah dichotomy. Persian religious dualism became the foundation of an ethical system that has lasted until this day. The reformation of Zarathustra retained the hundreds of Persian deities, assembling them into a complex hierarchical system of ‘Immortals’ and ‘Adored Ones’ under the rule of either Ahura- Mazda or Ahriman. Within this vast pantheon, Mithras gained the title of ‘Judger of Souls’. He became the divine representative of Ahura-Mazda on earth, and was directed to protect the righteous from the demonic forces of Ahriman. Mithras was called omniscient, undeceivable, infallible, eternally watchful, and never-resting. In the Avesta, the holy book of the religion of Zarathustra, Ahura-Mazda was said to have created Mithras in order to guarantee the authority of contracts and the keeping of promises. The name Mithras was, in fact, the Persian word for ‘contract’. The divine duty of Mithras was to ensure general prosperity through good contractual relations between men. It was believed that misfortune would befall the entire land if a contract was ever broken.

![Magi]()

Zoroastrian magi from Kerman during the Jashne Sadeh ceremonies (Source: Heritage Institute).

Ahura-Mazda was said to have created Mithras to be as great and worthy as himself. He would fight the spirits of evil to protect the creations of Ahura-Mazda and cause even Ahriman to tremble. Mithras was seen as the protector of just souls from demons seeking to drag them down to Hell, and the guide of these souls to Paradise. As Lord of the Sky, he took the role of psychopomp, conducting the souls of the righteous dead to paradise. According to Persian traditions, the god Mithras was actually incarnated into the human form of the Saviour expected by Zarathustra. Mithras was born of Anahita, an immaculate virgin mother once worshipped as a fertility goddess before the hierarchical reformation. Anahita was said to have conceived the Saviour from the seed of Zarathustra preserved in the waters of Lake Hamun in the Persian province of Sistan. Mithra’s ascension to heaven was said to have occurred in 208 B.C.E., 64 years after his birth. Parthian coins and documents bear a double date with this 64 year interval.

Mithras was ‘The Great King’ highly revered by the nobility and monarchs, who looked upon him as their special protector. A great number of the nobility took theophorous (god-bearing) names compounded with Mithras. The title of the god Mithras was used in the dynasties of Pontus, Parthia, Cappadocia, Armenia and Commagene by emperors with the name Mithradates. Mithradates VI, king of Pontus (northern what is known as Turkey) in 120-63 B.C.E. became famous for being the first monarch to practice immunization by taking poisons in gradually increased doses.

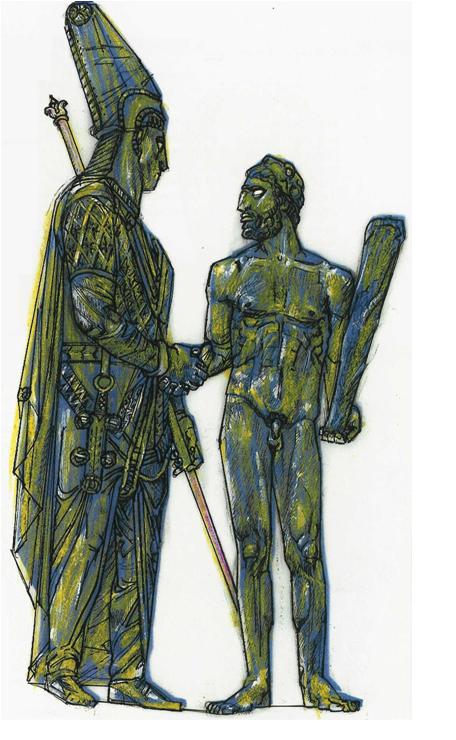

![Mithradates as Magus]()

An interesting relief at the ruins of Arsameia, the capital of the kingdom of Commagene in 1st century BC. King Mithradates I Kallinikos of Commagene (100–70 BC) dressed as the Zoroastrian Magi (left) shakes hands with the Greek god Hercules (Source: Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division; Photo originally by Mani Moradi). Note that Hercules in Commagene also represented the Persian god Artagnes. Commagene like the Pontus was a small post-Achaemenid Iranian kingdom in Anatolia situated squeezed between Parthia to its east and the expanding Roman Empire to its west. Various versions of Mithradates’ crown continue to appear among various mystical sects of Western Iran, notably Kurdistan.

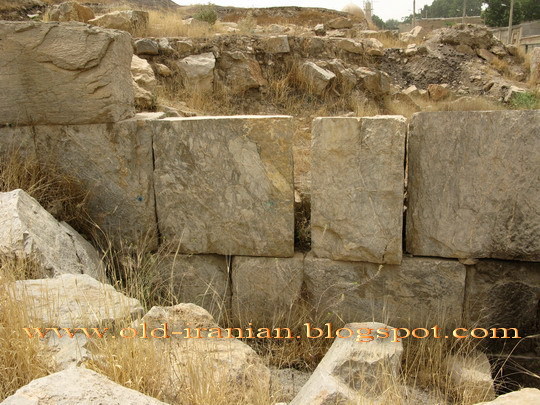

The terms mithridatism and mithridate (a pharmacological elixir) were named after him. The Parthian princes of Armenia were all priests of Mithras, and an entire district of this land was dedicated to the Virgin Mother Anahita. Many Mithraeums, or Mithraic temples, were built in Armenia, which remained one of the laststrongholds of Mithraism. The largest near-eastern Mithraeum was built in western Persia at Kangavar, dedicated to ‘Anahita, the Immaculate Virgin Mother of the Lord Mithras’. Other Mithraic temples were built in Khuzestan and in Central Iran near present-day Mahallat, where at the temple of Khorheh a few tall columns still stand. Excavations in Nisa, later renamed Mithradatkirt, have uncovered Mithraic mausoleums and shrines. Mithraic sanctuaries and mausoleums were built in the city of Hatra in upper Mesopotamia. West of Hatra at Dura Europos, Mithraeums were found with figures of Mithras on horseback. Persian Mithraism was more a collection of traditions and rites than a body of doctrines. However, once the Babylonians took the Mithraic rituals and mythology from the Persians, they thoroughly refined its theology. The Babylonian clergy assimilated Ahura-Mazda to the god Baal, Anahita to the goddess Ishtar, and Mithras to Shamash, their god of justice, victory and protection (and the sun god from whom King Hammurabi received his code of laws in the 18th century B.C.E.) As a result of the solar and astronomical associations of the Babylonians, Mithras later was referred to by Roman worshippers as ‘Sol invictus’, or the invincible sun.

![Mithras-Legacy]()

Mithras’ Enduring Legacy? (Left) Mithras at Taghe Bostan, Western Iran; (Middle) Deo Sol Invictus, Italy; (Right) The Statue of Liberty, Staten Island, New York.

The sun itself was considered to be “the eye of Mithras”. The Persian crown, from which all present day crowns are derived, was designed to represent the golden sun-disc sacred to Mithras. As a deity connected with the sun and its life-giving powers, Mithras was known as ‘The Lord of the Wide Pastures’ who was believed to cause the plants to spring forth from the ground. In the time of Cyrus and Darius the Great, the rulers of Persia received the first fruits of the fall harvest at the festival of Mehragan. At this time they wore their most brilliant clothing and drank wine. In the Persian calendar, the seventh month and the sixteenth day of each month were also dedicated to Mithras. The Babylonians also incorporated their belief in destiny into the Mithraic worship of Zurvan, the Persian god of infinite time and father of the gods Ahura-Mazda and Ahriman. They superimposed astrology, the use of the zodiac, and the deification of the four seasons onto the Persian rites of Mithraism.

“Astrology, of which these postulates were the dogmas, certainly owes some share of its success to the Mithraic propaganda, and Mithraism is therefore partly responsible for the triumph in the West of this pseudo-science with its long train of errors and terrors.” (Franz Cumont, French Mithraic researcher Les Mystères de Mithra, p.125).

![1-Taq-Bostan]()

Investiture of Ardashir II (r. 379-383) (center) by the supreme God Ahuramazda (right) with Mithra (left) standing upon a lotus (Ghirshman, 1962 & Herrmann, 1977). Trampled beneath the feet of Ahura-Mazda and Ardashir II is an unidentified defeated enemy (possibly Roman Emperor Julian). Of interest are the emanating “Sun Rays” from the head of Mithras. Note the object being held by Mithras, which appears to be a barsum, or perhaps some sort of diadem or even a ceremonial broadsword, as Mithras appears to be engaged in some sort of “knighting” of Ardashir II as he receives the “Farr” (Divine Glory) diadem from Ahura-Mazda (Picture source: Shahyar Mahabadi, 2004).

The Persians called Mithras ‘The Mediator’ since he was believed to stand between the light of Ahura-Mazda and the darkness of Ahriman. He was said to have 1000 eyes, expressing the conviction that no man could conceal his wrongdoing from the god. Mithras was known as the God of Truth, and Lord of Heavenly Light, and said to have stated:

“I am a star which goes with thee and shines out of the depths”.

Mithras was associated with Verethraghna, the Persian god of victory. He would fight against the forces of evil, and destroy the wicked. It was believed that offering sacrifices to Mithras would provide strength and glory in life and in battle. In the Avesta, Yasht 10, it reads that Mithras:

“spies out his enemies; armed in his fullest panoply he swoops down upon them, scatters and slaughters them. He desolates and lays waste the homes of the wicked, he annihilates the tribes and the nations that are hostile to him. He assures victory unto them that fit instruction in the Good, that honour him and offer him the sacrificial libations.”

Mithras was worshipped as guardian of arms, and patron of soldiers and armies. The handshake was developed by those who worshipped him as a token of friendship and as a gesture to show that you were unarmed. When Mithras later became the Roman god of contracts, the handshake gesture was imported throughout the Mediterranean and Europe by Roman soldiers.

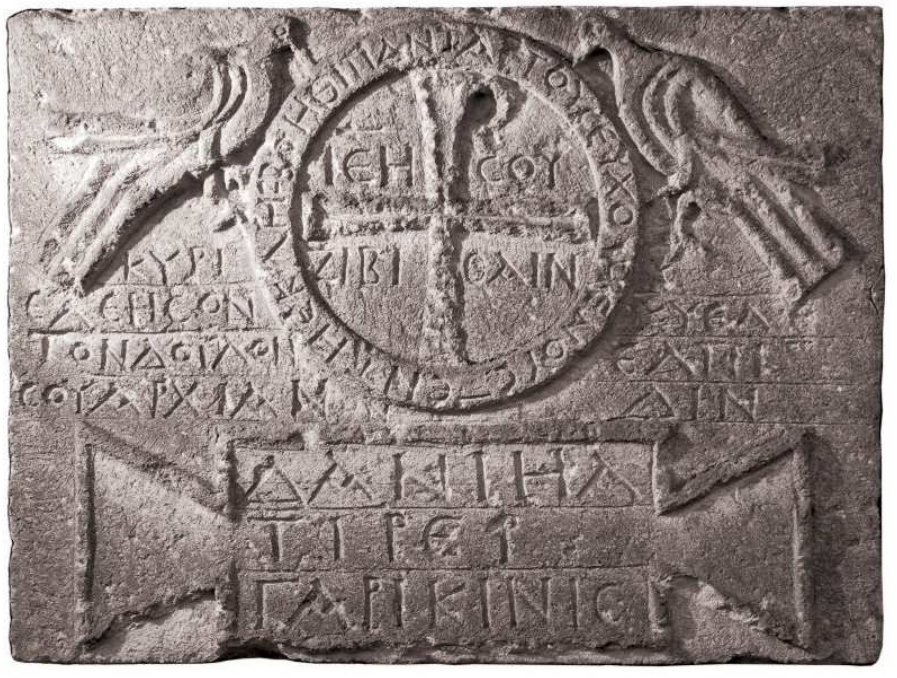

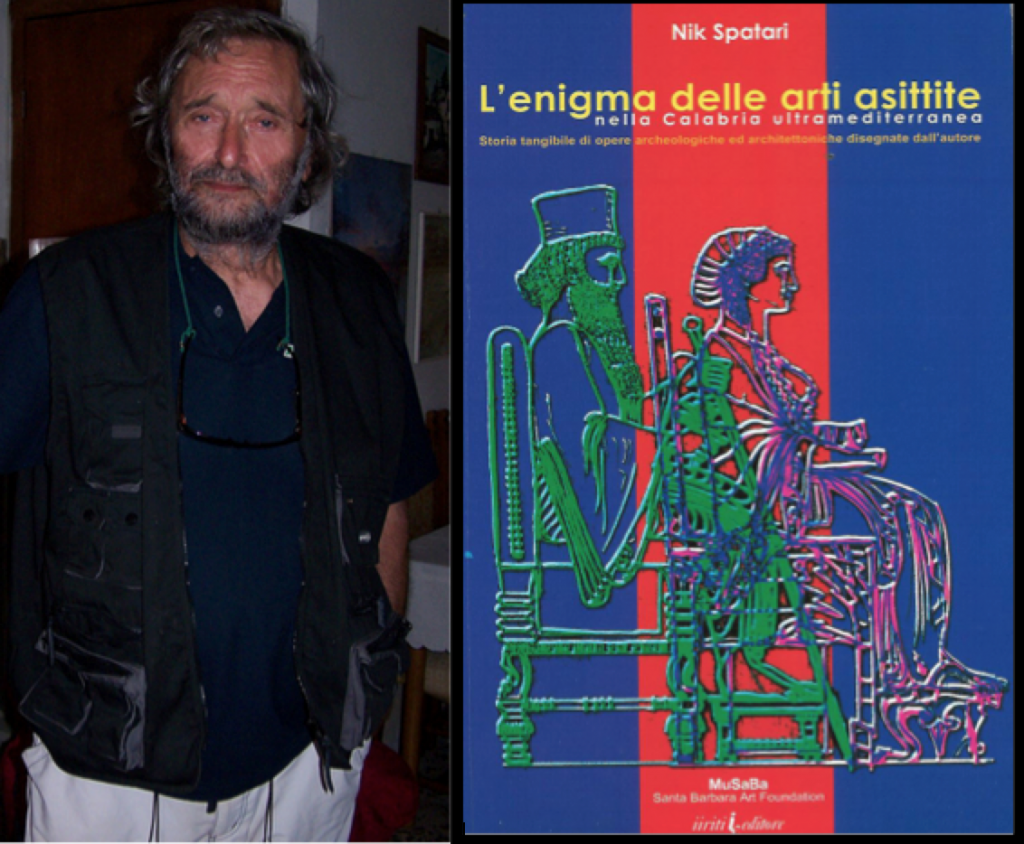

![Nik Spatari-Mithras]()

[Click to Enlarge] Nik Spatari’s drawing of the site of Eski Kale in Turkey (dated to circa 300 BCE) showing Mithras at left in Iranian attire shaking hands with the Hellenic God Zeus at right. This may be one of the first artistic depictions of the handshake symbolizing the “Payman” (pact).

In Armenian tradition, Mithras was believed to shut himself up in a cave from which he emerged once a year, born anew. The Persians introduced initiates to the mysteries in natural caves, according to Porphyry, the third century neoplatonic philosopher. These cave temples were created in the image of the World Cave that Mithras had created, according to the Persian creation myth. As ‘God of Truth and Integrity’, Mithras was invoked in solemn oaths to pledge the fulfillment of contracts and punish liars. He was believed to maintain peace, wisdom, honour, prosperity, and cause harmony to reign among all his worshippers.

![Garni Temple-Armenia]()

[Click to Enlarge] The Temple of Garni in Armenia. An example of Classical Armenian architecture of Hellenic inspiration, this Temple was first ordered to be built in dedication to Mithras by Tiridates I in approximately 66 CE. The god Mithras in time became merged with the Sol Invictus (Unconquered Sun) of the Roman Empire (Picture Source: Skyscraper City).

According to the Avesta, Mithras could decide when different periods of world history were completed. He would judge mortal souls at death and brandish his mace over hell three times each day so that demons would not inflict greater punishment on sinners than they deserved. Sacrificial offerings of cattle and birds were made to Mithras, along with libations of Haoma, a hallucinogenic drink used by Zoroastrian and Hindu priests, equated with the infamous hallucinogen ‘Soma’ described in the Vedic scriptures. Before daring to approach the altar to make an offering to Mithras, Persian worshippers were obliged to purge themselves by repeating purification rituals and flagellating themselves. These customs were continued in the initiation ceremonies of the Roman neophytes.

Expansion of the Faith

With the rapid expansion of the Persian Empire, the worship of Mithras spread eastward through northern India into the western provinces of China. In Chinese mythology, Mithras came to be known as ‘The Friend’. To this day, Mithras is represented as a military General in Chinese statues, and is considered to be the friend of man in this life and his protector against evil in the next. In India, Mithras was recognized as ‘God of Heavenly Light’ and an ally of Indra, King of Heaven. Mithras was often prayed to and invoked along with Varuna, the Hindu god of moral law and true speech. Jointly known as ‘Mitra-Varuna’, it was believed that together they would uphold order in the world while travelling in a shining chariot and living in a golden mansion with a thousand pillars and a thousands doors. Mithras was also praised in the Vedic hymns. Just as in the Zoroastrian Avesta, the Hindu scriptures recognized Mithras as ‘God of Light’, ‘Protector of Truth’, and ‘Enemy of Falsehood’. The worship of Mithras also extended westward through what is now Turkey to the borders of the Aegean Sea. A bilingual dedication to Mithras, written in Greek and Aramaic, was found engraved upon a rock in a wild pass near Farasha in the Turkish province of Cappadocia. Mithras was also the only Iranian god whose name was known in ancient Greece. A grotto located near the Greek town of Tetapezus was dedicated to Mithras, before it was transformed into a church. However, Mithraism never made many converts in Greece or in the Hellenized countries. That country never extended the hand of hospitality to the god of its ancient enemies. According to the Greek historian Plutarch (46-125 C.E.) Mithras was first introduced into Italy by pirates from Cilicia (Sout-East Turkey) who initiated the Romans into the secrets of the religion. These pirates performed strange sacrifices on Mount Olympus and practiced Mithraic rituals, which according to Plutarch “exist to the present day and were first taught by them”. However, there were many foreign cults in Italy at that time, and these early Mithraists did not attract much attention.

![-mithraeum]()

The Mithraeum of Seven Gates, Ostia (Source: Philip Coppens). As noted by Philip Coppens: “The Cult of Mithras, rather than Christianity, almost became the religion that dominated Western Europe. It failed, but intriguingly, we now hardly know anything about it”.

It is one of the great of ironies of history that Romans ended up worshipping the god of their chief political enemy, the Persians. The Roman historian Quintus Rufus recorded in his book History of Alexander that before going into battle against the ‘anti-Mithraean country’ of Rome, the Persian soldiers would pray to Mithras for victory. However, after the two enemy civilizations had been in contact for more than a thousand years, the worship of Mithras finally spread from the Persians through the Phrygians of Turkey to the Romans. The Romans viewed Persia as a land of wisdom and mystery, and Persian religious teachings appealed to those Romans who found the established state religion uninspiring – just as during the Cold War era of the 1960′s many American university students rejected western religious values and sought enlightenment in the established spirituality of Communist east-Asian “enemy countries”.

Mithras in the Roman Empire

“Let us suppose that in modern Europe the faithful had deserted the Christian churches to worship Allah or Brahma, to follow the precepts of Confucius or Buddha, or to adopt the maxims of the Shinto; let us imagine a great confusion of all the races of the world in which Arabian mullahs, Chinese scholars, Japanese bonzes, Tibetan lamas and Hindu pundits should all be preaching fatalism and predestination, ancestor-worship and devotion to a deified sovereign, pessimism and deliverance through annihilation – a confusion in which all those priests should erect temples of exotic architecture in our cities and celebrate their disparate rites therein. Such a dream, which the future may perhaps realize, would offer a pretty accurate picture of the religious chaos in which the ancient world was struggling before the reign of Constantine.” Among the Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism, At a time when Christianity was only one of several dozen foreign Eastern cults struggling for recognition in Rome, the religious dualism and dogmatic moral teaching of Mithraism set it apart from other sects, creating a stability previously unknown in Roman paganism. Early Roman worshippers imagined themselves to be keepers of ancient wisdom from the far east, and invincible heroes of the faith, ceaselessly fighting the powers of corruption. Mithraism quickly gained prominence and remained the most important pagan religion until the end of the fourth century, spreading Zoroastrian dualism throughout every province of the empire for three hundred years.

![-Mithraism-Map]()

Map of Mithraism in the Roman Empire at its greatest extent in the 1st to early 4th centuries CE (Source: Hinnells, 1988, p.77).

In those days, it was imperial policy to remove troops as far as possible from their country of origin in order to prevent local uprisings. A Roman soldier who, after several years of service in his native country had been promoted to the rank of centurion, was transferred to a foreign station where he was later assigned to a new garrison. This way, the entire body of centurions of any one legion constituted a microcosm of the empire. The vast extent of the Roman colonies formed links between Persia and the Mediterranean and caused the diffusion of the Mithraic religion into the Roman world. Mithraism became a military religion under the Romans. The many dangers to which the Roman soldiers were exposed caused them to seek the protection of the gods of their foreign comrades in order to obtain success in battle or a happier life through death. The soldiers adopted the Mithraic faith for its emphasis on victory, strength, and security in the next world. Temples and shrines were dedicated to Mithras across the empire.

In 67 B.C., the first congregation of Mithras-worshipping soldiers existed in Rome under the command of General Pompey. From 67 to 70 C.E., the legio XV Apollinaris, or Fifteenth Apollonian Legion, took part in suppressing the uprising of the Jews in Palestine. After sacking and burning the Second Temple in Jerusalem and capturing the infamous Ark of the Covenant, this legion accompanied Emperor Titus to Alexandria, where they were joined by new recruits from Cappadocia (Turkey) to replace casualties suffered in their victorious campaigns.

![Julian's failed invasion of Persia in 363 AD]()

An irony? Emperor Julian is killed during his failed invasion of Sassanian Persia in June 26, 363 CE. Above is a recreation of Sassanian Persia’s elite cavalry, the Savaran, and combat elephants as they would have appeared during Julian’s failed invasion. Note the rider in Mithraic attire bearing an unknown Sassanian 3-pronged symbol (Picture source: Farrokh, Plate D, -اسواران ساسانی- Elite Sassanian cavalry, 2005). It is possible that numbers of the Roman troops in Julian’s army also worshiped the Iranian god, Mithras!

After their transportation to the Danube with the veteran legionnaires, they offered sacrifices to Mithras in a semicircular grotto that they consecrated to him on the banks of the river. Soon, this first temple was no longer adequate and a second one was built adjoining a temple of Jupiter. As a municipality developed alongside the camp and the conversions to Mithraism continued to multiply, a third and much larger Mithraeum was erected towards the beginning of the second century. This temple was later enlarged by Diocletian, Emperor from 284-305 C.E. Diocletian rededicated this sanctuary to Mithras, giving him the title “The Protector of the Empire”. Five Mithraeums were found in Great Britain, where only three Roman legions were stationed. Remains were discovered in London near St. Paul’s Cathedral, in Segontium in Wales, and three were found along Hadrian’s Wall in Northern England. Mithraism also reached Northern Africa by Roman military recruits from abroad. By the second century, the worship of Mithras had spread throughout Germany due to the powerful army that defended this territory. The greatest number of Mithraeums in the western world were discovered in Germany. An inscription has been found of a centurion’s dedication to Mithras dating back to the year 148 C.E. One of the most famous Mithraic bas-reliefs, showing twelve scenes from the life of the god, was discovered in Neuenheim, Germany in 1838. When Commodus (Emperor from 180-192 C.E.) was initiated into the Mithraic religion, there began an era of strong support of Mithraism that included emperors such as Aurelian, Diocletian, and Julian the Apostate, who called Mithras “the guide of the souls”. All of these emperors took the Mithraic titles of ‘Pius’, ‘Felix’, and ‘Invictus’ (devout, blessed, and invincible). From this point on, Roman authority legitimized their rule by divine right, as opposed to heredity or vote of the Senate. The Babylonian astrological influence within Mithraism established a solar henotheism as the leading religion at Rome. In 218 C.E. the Roman Emperor Heliogabalus (placed upon the throne at age 14) attempted to elevate his god, the Baal of Emesa to the rank of supreme divinity of the empire by subordinating the entire ancient pantheon. Heliogabalus was soon assassinated for his aspiration of a solar henotheism, but half a century later his attempt inspired emperor Aurelian to initiate the worship of the Sol invictus. Worshipped in an elaborate temple, magnificent plays were held in honour of this deity every fourth year. Sol invictus was also elevated to the supreme rank in the divine hierarchy, and became the special protector of the emperors and the empire. Many Mithraic reliefs showed scenes of Mithras and Sol sharing a banquet over a table draped with the skin of the bull. Soon after, the title of Sol invictus was transferred to Mithras. The Roman emperors formally announced their alliance with the sun and emphasized their likeness to Mithras, god of its divine light. Mithras was, also, unified with the sun-god Helios, and became known as ‘The Great God Helios-Mithras’. Emperor Nero adopted the radiating crown as the symbol of his sovereignty to exemplify the splendour of the rays of the sun, and to show that he was an incarnation of Mithras. He was initiated into the Mithraic religion by the Persian Magi brought to Rome by the King of Armenia. Emperors from that time onwards proclaimed themselves destined to the throne by virtue of having been born with the divine ruling power of the sun.

The Rites of Mithraic Initiation

Upon enlistment, the first act of a Roman soldier was to pledge obedience and devotion to the emperor. Absolute loyalty to authority and to fellow soldiers was the cardinal virtue, and the Mithraic religion became the ultimate vehicle for this fraternal obedience. The Mithras worshippers compared the practice of their religion to their military service. All of the initiates considered themselves sons of the same father owing to one another a brother’s affection. Mithras was a chaste god, and his worshippers were taught reverence for celibacy (a convenient trait for soldiers to maintain). The spirit of camaraderie (and celibacy) was to be continued in the Roman Empire by the Christian belief in neighborly love and universal charity. However, the worshippers of Mithras did not lose themselves in a contemplative mysticism like the followers of other near-eastern sects. Their morality particularly encouraged action, and during a period of war and confusion, they found stimulation, comfort and support in its tenets. In their eyes of the Roman soldiers, resistance to evil deeds and immoral actions became just as valued as victory in glorious military exploits. They would fight the powers of evil in accordance with the ideals of Zoroastrian dualism, in which life was conceived as a struggle against evil spirits. By supplying a new conception of the world, Mithraism gave new meaning to life by determining the worshipper’s beliefs concerning life after death. The struggle between good and evil was extended into the afterworld, where Mithras ensured the protection of his followers from the powers of darkness. It was believed that Mithras would judge the souls of the dead and lead the righteous into the heavenly regions where Ahura-Mazda reigned in eternal light. Mithraism brought the assurance that reverence would be rewarded with immortality.

![Mithra temple-Carrawburgh]()

Remains of the Temple of Mithra at Carrawburgh, England (Source: Britain Express). The culture 0f Mithras continues to endure among the Iranians (within Iran and the Kurds of the Near East beyonf modern-day Iran. The Kurds speak West Iranian languages (i.e. Kurmnaji, Gowrani, etc.) that are akin to Persian and Luri.

Mithraism was an archetypal mystery cult and secret society. Like the rites of Demeter, Orpheus, and Dionysus, the Mithraic rituals admitted candidates by secret ceremonies, the meaning of which was known only to the initiated. Like all other institutionalized initiation rites of the past and present, this mystery cult allowed the initiates to be controlled and put under the command of their leaders. Preceding initiation into the Mithraic fold, the neophyte had to prove his courage and devotion by swimming across a rough river, descending a sharp cliff, or jumping through flames with his hands bound and eyes blindfolded. The initiate was also taught the secret Mithraic password, which he was to use to identify himself to other members, and which he was to repeat to himself frequently as a personal mantra. Mithraic worshippers believed that the human soul descended into the world at birth. The goal of their religious quest was to achieve the soul’s ascent out of the world again by gaining passage through seven heavenly gates, corresponding to seven grades of initiation. Therefore, being promoted to a higher rank in the religion was believed to correspond to a heavenly journey of the soul. Promotion was obtained through submission to religious authority (kneeling), casting off the old life (nakedness), and liberation from bondage through the mysteries.

![Bible_museum_-_Mithrasheiligtum]()

A reconstruction of a Mithraeum (Darb-e Mehr) depicting the stages of ascension on the floor as alluded to in the previous photo this posting (Source: Wolfgang Sauber for Public Domain). Note the placing of grapes (right side); grapes continue to signify vitality and renewal in Iran, Italy, Anatolia and the Caucasus.

The process of Mithraic initiation required the symbolic climbing of a ceremonial ladder with seven rungs, each made of a different metal to symbolize the seven known celestial bodies. By symbolically ascending this ceremonial ladder through successive initiations, the neophyte could proceed through the seven levels of heaven. The seven grades of Mithraism, were: Corax (Raven), Nymphus (Male Bride), Miles (Soldier), Leo (Lion), Peres (Persian), Heliodromus (Sun-Runner), and Pater (Father); each respective grade protected by Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, the Moon, the Sun, and Saturn. The lowest degree of initiation into the grade of Corax symbolized the death of a new member, from which he would arise reborn as a new man. This represented the end of his life as an unbeliever, and cancelled previous allegiances to the other unacceptable beliefs. The title Corax (Raven) originated with the Zoroastrian custom of exposing the dead on funeral towers to be eaten by carrion birds, a custom continued today by the Parsis of India, the descendants of the Persian followers of Zarathustra. Further initiation involved the clashing of cymbals, beating of drums, and the unveiling of a statue of Mithras. The initiate drank wine from the cymbal to recognize it as the source of ritual ecstasy. Next, he ate a small morsel of bread placed on a drum, to signify his acceptance of Mithras as the source of his food. This bread had been exposed to the rays of the sun, so by eating the bread the worshipper was partaking of the divine essence of the sun itself. The initiate would also offer a loaf of bread and cup of water to the statue of Mithras. When a neophyte reached the degree of Miles (soldier), he was offered a crown, which he had to reject with the saying:

“Only Mithras is my crown”.

The indelible mark of a cross, symbol of the sun, was then branded on his forehead with a hot iron to symbolize his ownership by the deity, and he would renounce the social custom of wearing a wreath. From then on, the neophyte belonged to the sacred militia of ‘The Invincible God Mithras’. All family ties were severed and only fellow initiates were to be considered brothers.

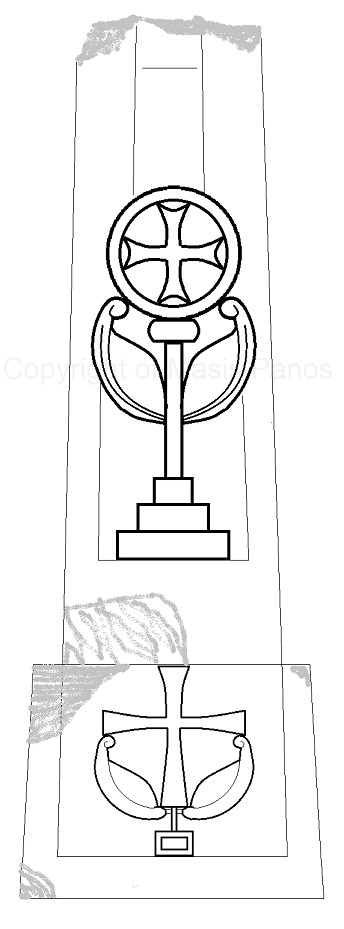

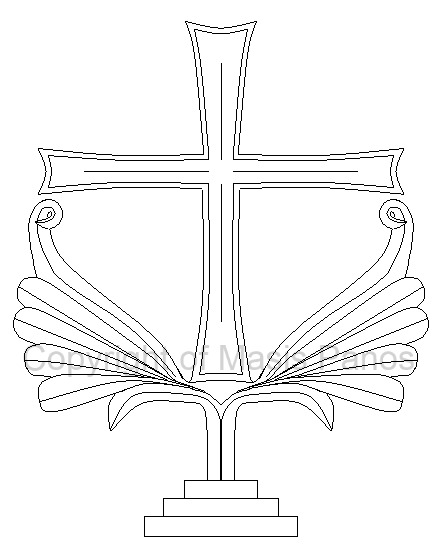

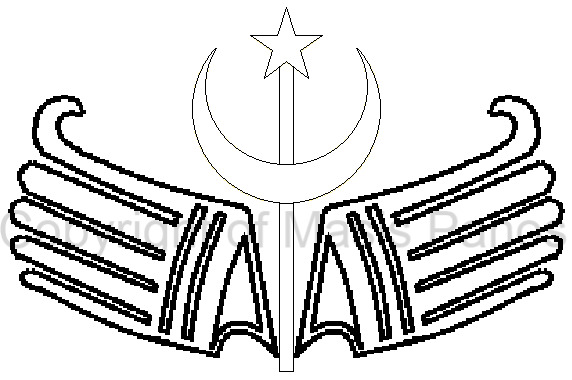

![Mithraism-Rome]()

[Click to Enlarge] The stages of Roman Mithraism: Stage 1: Cerax (Raven); – Stage 2-Nymphos (Bride); Stage 3-Miles (Soldier); Stage 4-Leo (Lion); Stage 5-Perses (Persian); Stage 6- Heliodrommus (Sun-Runner); Stage 7-Pater (Father) (Picture sources: Hinnels, 1988). Note that term “Bride” often used to denote “Nymphos” for the second stage is simplistic at best. The Latin term should actually be in the feminine “Nymphe” and not the masculine “Nymphos” or a male bride which possibly may suggest something of a mystical male-female fusion. The reasons for this are not as yet clear, but it seems consistent with Roman or Western (as opposed to the original Iranian) Mithraism which is believed to have excluded women from its rituals and membership. Note that in the final grade (Stage VII-Father) there is a distinct Persian cap symbolizing the cap of Mithras (Picture sources: Cerax, Nymphos, Miles from Hinnels, 1985; Leo, Persian, and Heliodrommus, and Pater in Public Domain).

Worshippers used caves and grottos as temples wherever possible, or at least gave temples the internal appearance of caves or of being subterranean by building steps leading down to the entrance. They took part in masquerading as animals, such as ravens and lions, and inserted passages into their ritual chants that were devoid of any literal meaning.

All of these rites that characterized Roman Mithraism originated in ancient prehistoric ceremonies.

During the rituals, the evolution of the universe and the destiny of mankind was explained. The service consisted chiefly of contemplating the Mithraic symbolism, praying while knelt before benches, and chanting hymns to the accompaniment of flutes. Hymns were sung describing the voyage of Mithras’ horse-drawn chariot across the sky.

Invokers and worshippers of Mithras prayed:

“Abide with me in my soul. Leave me not [so] that I may be initiated and that the Holy Spirit may breathe within me.”

Animal sacrifices, mostly of birds, were also conducted in the Mithraeums. The Mithraic clergy’s duty was to maintain the perpetual holy fire on the altar, invoke the planet of the day, offer the sacrifices for the disciples, and preside at initiations. The Mithraic priests were known as Patres Sacrorum, or Fathers of the Sacred Mysteries.

They were mystically designated with the titles Leo and Hierocorax, and presided over the priestly festivals of Leontica (the festival of lions), Coracica (the festival of ravens), and Hierocoracica (the festival of sacred ravens). The great festival of the Mithraic calendar was held on December the 25th, and the 16th of every month was kept holy to Mithras. The first day of the week was dedicated to the sun, to whom prayers were recited in the morning, noon, and evening.

![Reconstruction of Mithra ceremony]()

An interesting reconstruction of a Mithraic ceremony in at the Mithraic temple of Osterburken, Germany (Mithraeum.eu).

Services were held on Sundays, in which bells were sounded and praises were offered to Mithras. On great occasions, the ‘soldiers of Mithras’ took part in the sacrament of bread and wine as sacred bulls were sacrificed.

The Taurobolium

While Mithras was worshipped almost exclusively by men, most of the wives and daughters of the Mithraists took part in the worship of Magna Mater, Ma-Bellona, Anahita, Cybele, and Artemis. These goddess religions practiced a regeneration ritual known as the Taurobolium, or bull sacrifice, in which the blood of the slaughtered animal was allowed to fall down upon the initiate, who would be lying, completely drenched in a pit below. As a result of their association with practitioners of this rite, Mithraists soon adopted the Taurobolium ritual as their own. This baptism of blood became a renewal of the human soul, as opposed to mere physical strength.

!["Tauroctony" - Mithras slaying a bull]()

[Click to Enlarge] Another depiction of Mithras with Persian dress slaying the sacred bull at the Vatican Museum in Rome (Source: Tertullian.org). Note the dog and serpent heading towards the gushing blood pouring down from the bull’s neck as the the scorpion heads towards the dying bull’s testicles.

Mithraic baptism wiped out moral faults; the purity aimed at had become spiritual. The descent into the pit was regarded as symbolic burial, from which the initiate would emerge reborn, purified of all his crimes and regarded as the equal of a god. Those who made it through the Taurobolium were revered by their brethren, and accepted in the fold of Mithraism.

“The taurobolium had become a means of obtaining a new and eternal life; the ritualistic ablutions were no longer external and material acts, but were supposed to cleanse the soul of its impurities and to restore its original innocence; the sacred repasts imparted an intimate virtue to the soul and furnished sustenance to the spiritual life” (Franz Cumont Les Mystères de Mithra).

The bull has been exalted throughout the ancient world for its strength and vigour. Greek myths told of the Minotaur, a half-man half-bull monster who lived in the Labyrinth beneath Crete, and took an annual sacrifice of six young men and six maidens before being slain by the hero Theseus. Minoan artwork depicted nimble acrobats leaping bravely over the backs of bulls. The altar in front of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem was adorned with bull horns believed to be endowed with magical powers. The bull was also one of the four tetramorphs, the symbols later associated with the four gospels. The mystique of this powerful animal still survives today in the ritualistic bull-fighting of Spain and Mexico, and in the rodeo bull-riding of the U.S. The bull was an obvious representation of masculinity by nature of its size, strength, and sexual power. At the same time, the bull symbolized lunar forces by virtue of its horns and earthly forces by virtue of its powerful root to the ground.

![Santa_Maria_Capua_Vetere_Mithraeum_Tauroctony]()

[Click to Enlarge] Depiction of Mithras with Persian dress of the (Parthian and Early-Mid Sassanian era type) slaying the sacred bull at the Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Source: Dom De Felice for Public Domain). Note the dog and serpent.

The ritual sacrifice of the bull symbolized the penetration of the feminine principle by the masculine. The slaying of the bull represented the victory of man’s spiritual nature over his animality; parallel to the symbolic images of Marduk slaying Tiamut, Gilgamesh killing Humbaba, Michael subduing Satan, St. George slaying the dragon, the Centurion piercing Christ’s side, Lewis Carroll’s “beamish boy” slaying the Jabberwocky, and Sigourney Weaver slaying the Alien.

According to the archetypal hero myth recited in Roman Mithraic rituals, the infant Mithras formed an alliance with the sun and set off to kill the bull, the first living creature ever created. While the bull was grazing in a pasture, Mithras seized it by the horns and dragged it into a cave. The bull soon escaped, but was recaptured when Mithras was given the command by the raven, messenger of the sun, to slay the bull. With the help of his dog, Mithras succeeded in overtaking the bull and dragging it again in the cave. Then, seizing it by the nostrils, he plunged deep into its flank with his knife. As the bull died, the world came into being and time was born. From the body of the slain beast sprang forth all the herbs and plants that cover the earth.

![mithras-the-bringer-of-light]()

A Roman version of the statue of Mithras “Bringer of Light” in a Mithraic temple in Ostia, Italy (Consult, Hinnells, 1988, p.83). Note the opening on the ceiling just above Mithras, allowing the sun rays to “illuminate” the god. Mithras in Iranian mythology is the bringer of light and justice as well as a manifestation of the eternal sun.

From the spinal cord of the animal sprang wheat to produce bread, and from the blood came the vine to produce wine. The shedding of the sacrificial blood brought great blessings to the world, which Ahriman tried to prevent. The struggle between good and evil, which at that moment it first began, was to continue until the end of time.

“This ingenious fable carries us back to the very beginnings of civilization. It could never have risen save among a people of shepherds and hunters with whom cattle, the source of all wealth, had become an object of religious veneration”.

Mithraic sculpture depicted the Taurobolium with invariable consistency. Mithras was often depicted in the cave kneeling on the back of the bull, dagger in hand, wearing a flowing cape and Phrygian cap (the rounded, conical hats currently en vogue amongst rap-music fans). He was shown pulling back the bull’s head by its nostrils and stabbing it with the dagger, back foot extended over the bull’s right leg. A dog and a snake were shown leaping into bull’s wound, representing the dualistic conflict of good and evil at the moment of creation. A scorpion was shown at the bull’s genitals, depicting evil seeking to destroy life at its source. Ears of corn sprung from the tail of the bull representing victory of good over evil. During the celebration of the vernal equinox, the Phrygian priests of the Great Mother attributed the blood shed in the Taurobolium to the redemptive power of the blood of the Divine Lamb shed on the Christian Easter. It was maintained that the dramatic Taurobolium purification ritual was more effective than baptism. The food that was taken during the mystic feasts was likened to the bread and wine of the communion; the Mother of the Gods (Magna Mater) received greater worship than the Mother of God (Mary), whose son also had risen again. An inscription in the Mithraeum under the Church of Santa Prisca in Rome referred to Mithras saving men by shedding the eternal blood of the bull. On the very spot on which the last Taurobolium took place at the end of the fourth century, in the Phrygianum, today stands the Vatican’s St. Peter’s Basilica.

![-Tauroctony_Heddernheim]()

Relief of Mithras and the Tauroctony from the “Heidenfeld” Mithraeum of Heddernheim, Germany, presently located in Wiesbaden (Source: Dierk Schaefer for Public Domain).

The Evolution

“As the religious history of the empire is studied more closely, the triumph of the church will, in our opinion, appear more and more as the culmination of a long evolution of beliefs. We can understand the Christianity of the fifth century with its greatness and weaknesses, its spiritual exaltation and its puerile superstitions, if we know the moral antecedents of the world in which it developed” (Franz Cumont).

As the final pagan religion of the Roman Empire, Mithraism paved a smooth path for Christianity by transferring the better elements of paganism to this new religion. After Constantine, Emperor from 306-337 C.E., converted on the eve of a battle in 312 C.E., Christianity was made the state religion. All emperors following Constantine were openly hostile towards Mithraism. The religion was persecuted on the grounds that it was the religion of Persians, the arch-enemies of the Romans. The absurdity with which Christianity enveloped Roman paganism was characterized by the early Church writer Tertullian (160-220 C.E.), who noticed that the pagan religion utilized baptism as well as bread and wine consecrated by priests. He wrote that Mithraism was inspired by the devil, who wished to mock the Christian sacraments in order to lead faithful Christians to hell. Nonetheless, Mithraism survived up to the fifth century in remote regions of the Alps amongst tribes such as the Anauni, and has managed to survive in the near-east until this day.

Mithras is still venerated today by the Parsis, the descendants of the Persian Zoroastrians now living mainly in India. Their temples to Mithras are now called ‘dar-i Mihr’ (The Court of Mithras). A scholar living among Parsis in Karachi, Pakistan reported that a Parsi mother, finding one of her grandchildren fighting with a younger child, told him to remember that Mithras was watching and would know the truth. Upon initiation, Parsi priests are given a ‘Gurz’, the symbolic Mace of Mithras, to represent the priestly duty to make war on evil. The priests continue to conduct their most sacred rituals under Mithra’s protection.

In Iran, up until 1979, traditional Mithraic holidays and customs still continued to be officially practiced, however the celebrations have continued despite the current Iranian establishment’s pan-Islamic outlook . The Iranian New Year celebration called ‘Now-Ruz’ takes place during the spring and continues for thirteen days. During this time Mehr (Mithras) is extolled as ancient god of the sun. The ‘Mihragan’ festival in honor of Mithras, Judge of Iran, also runs for a period of 5 days with great rejoicing and in a spirit of deep devotion.

![MegreganShooshtarNiknam3]()

Zoroastrians engage in the celebration of Mehregan or festival of Mithras in Shushtar, Iran (Picture source: Kouroush Niknam). For more see article by Massoume Price entitled “Mehregan”…

Manicheans and Later Heresies

Back in early medieval Europe, a form of Mithraism had managed to survive for centuries beyond the edicts of Constantine. Even when it had been dethroned by Christianity, the Mithraic faith lived on in dignified opposition by mutating into a Christian heresy known as Manichaeism, which was to become a source of strife and bloodshed right down to the Middle Ages. The Persian dualism of Zarathustra introduced such strong principles into Europe that they continued to exert an influence long after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Manichean faith succeeded as an heir to Mithraism, spreading within decades throughout the territories once covered by Mithraism in Asia and throughout the Mediterranean, eventually encompassing regions from China to North Africa, Spain, and Southern France.

![Mani-Portrait]()

A portrait of the prophet Mani (216-274 or 277 CE) (Source: Great Thoughts Treasury). Mani viewed himself as the final seal of the prophets, completing the previous religious messages of Zoroaster, Christ and the Buddha. His theological views, especially with respect to evil and its relation to material existence incurred the wrath of not only the Zoroastrian Magi of his Persian homeland but also that of the later Christians and Emperors of China.

Mani was born in 216 C.E. nearly 500 years after the incarnation of Mithras, and given the title ‘The Seal of the Prophets’ (a title since given to Mohammed by Islam). He was also called the Bagh, or the Lord to succeed Mithras. Mani preached a dualistic theological system emphasizing the purity of the spirit and the impurity of the body. He believed that the universe was controlled by the opposing powers of good and evil which had become temporarily intertwined, but at a future time would be separated and return to their own realms. Manichaean ethics focused on freeing the soul from the body and opposing material and physical pleasures.Mani’s followers attempted to assist this separation by leading ascetic lives, preaching renunciation of the world, and discouraging marriage and procreation.

![Map of Manicheaism]()

Map detailing the spread of Manicheaism (Source: Trans Cultural Studies).

Ironically, Manichaeism was denounced in the west by the Papacy as a dangerous heresy considered detrimental to social life and common human institutions. It was also condemned in Persia for similar reasons. Mani was persecuted and finally put to death in 276 C.E, as were many of his followers. Regardless, Manichaeism spread widely and was a major religion in the East until the 14th century. It died out in the West by the 6th century, but later led to the creation of several early Christian heresies, such as the those of the Cathars and the Albigenses.

![Mani-Cathars]()

Medieval depiction of a dispute between Saint Dominic and the Cathars, also known as the Albigensians (Source: Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at The University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division). Interestingly, the Cathars denied charges of being Manicheans, yet their belief systems were wholly consistent with Mani’s teachings.

The Albigenses were a heretical Christian sect whose influence became widespread in Southern France around the year 1200 C.E. Its theology was based entirely upon Manichean dualism. The Dominican Order was founded in 1205 in order to combat this heresy. Following the assassination of the papal legate in the year 1208, Pope Innocent III declared a crusade against the Albigenses. This developed into a political conflict with civil war between the north and south of France lasting until 1229. The Knights Templar, a religious military order founded by Crusaders in Jerusalem in 1118, came into contact with Manichean heretics who despised the Cross, regarding it as the instrument of Christ’s torture. This tenet was believed to have been adopted by the Templars, who were suppressed and charged with blasphemy in 1312 for committing homosexual acts, worshipping the demon Baphomet, and ritually spitting upon crucifixes. To this day, the Knights Templar have been emulated by dozens of mystical sects and secret societies, including the Freemasons, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the notorious Ordo Templi Orientallis reformulated by Alistair Crowley.

Conclusion

“If Christianity had been checked in its growth by some deadly disease, the world would have become Mithraic” [Joseph Renan, French religious historian and critic Marc-Aurèle et la fin du monde antique]

The Mithraic legacy resulted in customs still carried out today, including the handshake and the wearing of the crown by the monarchy. Worshippers of Mithras were the first in the western world to preach the doctrine of divine right of kings. It was the worship of the sun, combined with the theological dualism of Zarathustra, that disseminated the ideas upon which the Sun-King Louis XIV (1638-1715) and other deified sovereigns of the West maintained their monarchial absolutism. Of all the Roman pagan religions, none was so severe as Mithraism. None attained an equal moral elevation, and none could have had so strong a hold on mind and heart as the worship of this sun god and saviour. The major competitor with Christianity during the second and third centuries C. E., not even during the Moslem invasions had Europe come closer to adopting an Eastern religion than when Diocletian officially recognized Mithras as the protector of the Roman Empire. But in the end, Christianity finally became the champion of the inevitable conflict with the Zoroastrian faith for the dominion of the known world.

In theory, a proper coup-d’etat by the Mithras-worshipping Roman centurions could have prevented the Emperor Constantine from establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. Mithraism could quite possibly have survived through the following centuries with the theological assistance of the Manichean Heresy and its various offshoots, assuming that the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth had somehow have been simultaneously quashed (possibly through an increased number of crucifixions). With the absence of Christianity due to the continuation of Mithraism in the west, the rise of Islam may similarly have been prevented in the seventh century, and the violence of the crusades need not have occurred. Assuming that Islam had not enveloped Persia, the worship of Mithras could have continued within the pantheon of Zarathustra.

Consequently, Mithraism would have made an even stronger indentation upon the pantheons of India and China, and possibly spread beyond to other far-eastern countries. Columbus set sail during the Inquisition, another savage event representing the culmination of over a thousand years of European Christianity. Had Mithraism survived the millennium until the year 1492, the Indigenous people of the Americas would have been exposed to Mithraic worshippers instead of Catholic missionaries. Quite possibly, the Taurobolium would have been transposed upon the buffalo hunt rituals of the Plains Indians and the sacrificial ceremonies of the Maya, Inca, and Aztec, and these great empires would not have been annihilated by the brutal European conquerors who plundered in the name of King and Christ.

Let us play quantum physics through manipulating causality and further extending this ‘What If?’ scenario (and selectively ignoring countless variables) it is possible to reconstruct our current North American society with Mithraism in place of Christianity as the predominant religion and cultural driving force. After all, best selling author Mary Stewart used the concept of the local revival of Mithraism in medieval Britain for her novel Merlin of the Crystal Cave.

The great Mithraic researcher Franz Cumont also commented extensively on the possibility that Mithraism had survived beyond Constantine:

”The morals of the human race would have been but little changed, a little more virile perhaps, a little less charitable, but only a shade different. The erudite theology taught by the mysteries would obviously have shown a laudable respect for science, but as its dogmas were based upon a false physics it would apparently have insure the persistence of an infinity of errors. Astronomy would not be lacking, but astrology would have been unassailable, while the heavens would still be revolving around the earth to accord with its doctrines. The greatest danger, would have been that the Caesars would have established a theocratic absolutism supported by the Oriental ideas of the divinity of kings. The union of throne and altar would have been inseparable, and Europe would never have known the invigorating struggle between church and state. But on the other hand the discipline of Mithraism, so productive of individual energy, and the democratic organization of its societies in which senators and slaves rubbed elbows, contain a germ of liberty. While these contrasting possibilities may be interesting, it is hard to find a mental pastime less profitable than the attempt to remake history and to conjecture on what might have been had events proved otherwise.”

Bibliography

Beny, Roloff. Iran: Elements of Destiny. McClelland and Stewart Ltd. London, 1978.

Cumont, Franz. Les Mystères de Mithra. Dover Publications, Inc.,New York, 1956.

Cumont, Franz. The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism. Dover Publications, Inc. New York, 1956.

Eliade, Mircea. Patterns in Comparative Religion. The World Publishing Company. Cleveland, 1958.

Hinnells, John R. Persian Mythology. Peter Bedrick Books. New York, 1985.

Perowne, Stewart. Roman Mythology. Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. London, 1969.

[Click to Enlarge] -مراسم جشن آذرگشسب در اتشکده ای در آذربایجان- Celebration ceremonies at Ādur-Gushnasp in Iran’s Azarbaijan province (Photo forwarded to Kavehfarrokh.com by Ms. Kimia Behzadi on November 23, 2013 – original photo by Sima Mehrazar). This is the Gahanbar ceremony in which the “Lork” has received holy Avestan prayers, and is now being distributed among the congregation. Iran’s pre-Islamic cultural traditions have endured across the centuries.

[Click to Enlarge] -مراسم جشن آذرگشسب در اتشکده ای در آذربایجان- Celebration ceremonies at Ādur-Gushnasp in Iran’s Azarbaijan province (Photo forwarded to Kavehfarrokh.com by Ms. Kimia Behzadi on November 23, 2013 – original photo by Sima Mehrazar). This is the Gahanbar ceremony in which the “Lork” has received holy Avestan prayers, and is now being distributed among the congregation. Iran’s pre-Islamic cultural traditions have endured across the centuries. An excellent overview of the site of the site of Ādur-Gushnasp or Shiz (modern-day Takhte Suleiman) (Picture Source: Iran Atlas). The Ādur-Gushnasp sacred fire was dedicated to the Arteshtaran (Elite warriors) of the Sassanian Spah (Modern Persian: Sepah = Army).

An excellent overview of the site of the site of Ādur-Gushnasp or Shiz (modern-day Takhte Suleiman) (Picture Source: Iran Atlas). The Ādur-Gushnasp sacred fire was dedicated to the Arteshtaran (Elite warriors) of the Sassanian Spah (Modern Persian: Sepah = Army).  [Click to enlarge] A reconstruction of the late Sassanians at Ādur Gušnasp or Shiz (Takht e Suleiman in Azarbaijan, northwest Iran) by Kaveh Farrokh (painting by the late Angus Mcbride) in Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی-. To the left rides a chief Mobed (a top-ranking Zoroastrain priest or Magus), General Shahrbaraz (lit. “Boar of the realm”) is situated in the center and Queen Boran (Poorandokht) leads to the right.

[Click to enlarge] A reconstruction of the late Sassanians at Ādur Gušnasp or Shiz (Takht e Suleiman in Azarbaijan, northwest Iran) by Kaveh Farrokh (painting by the late Angus Mcbride) in Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی-. To the left rides a chief Mobed (a top-ranking Zoroastrain priest or Magus), General Shahrbaraz (lit. “Boar of the realm”) is situated in the center and Queen Boran (Poorandokht) leads to the right.  [Click to Enlarge] An excellent view of the edge of the lake at Ādur-Gushnasp (Photo Source: Public Domain).

[Click to Enlarge] An excellent view of the edge of the lake at Ādur-Gushnasp (Photo Source: Public Domain). [Click to Enlarge]One of the structures at Takhte Suleiman (Picture Source: World Historia).

[Click to Enlarge]One of the structures at Takhte Suleiman (Picture Source: World Historia). [Click to Enlarge] The ancient Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple – Zoroastrian Mobads Sohrab Hengami and Mehrab Vahidi are engaged in the recitation of the Holy Avesta (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).

[Click to Enlarge] The ancient Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple – Zoroastrian Mobads Sohrab Hengami and Mehrab Vahidi are engaged in the recitation of the Holy Avesta (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar). [Click to Enlarge] The Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple. After the prayers are concluded, a “Damavaz” (a ceremony participants) holds aloft the censer containing fire and incense in his hand to pass around the congregation. As this is done, the Damavaz repeats the Avesta term “Hamazour” (translation: Let us unite in good deeds). Participants first move their hands over the fire and then over their faces: this symbolizes their ambition to unite in good works and the spread of righteousness (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).

[Click to Enlarge] The Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple. After the prayers are concluded, a “Damavaz” (a ceremony participants) holds aloft the censer containing fire and incense in his hand to pass around the congregation. As this is done, the Damavaz repeats the Avesta term “Hamazour” (translation: Let us unite in good deeds). Participants first move their hands over the fire and then over their faces: this symbolizes their ambition to unite in good works and the spread of righteousness (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).[Click to Enlarge] Round columns at Takhte Suleiman (Photo Source: Novice View).

[Click to Enlarge] One of the participants at the Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar).

[Click to Enlarge] One of the participants at the Gahanbar ceremony at the Azargoshasb Fire Temple (Photo Source: Sima Mehrazar). [Click to Enlarge] One of the archways at Ādur-Gushnasp (Picture Source: World Historia).

[Click to Enlarge] One of the archways at Ādur-Gushnasp (Picture Source: World Historia).

Worshiped fire and small fires stand in line in the background cells (1865) (Source: Farroukh Jorat).

Worshiped fire and small fires stand in line in the background cells (1865) (Source: Farroukh Jorat).

Sedreh-Pushi ceremony of a group of Turkish Kurds and Iranians in Istanbul who are recent converts to Zoroastrianism (Source:

Sedreh-Pushi ceremony of a group of Turkish Kurds and Iranians in Istanbul who are recent converts to Zoroastrianism (Source:

The Egyptian Trinity (right to left): Goddess Isis, Osiris (Isis’ husband) and their son Horus, statuette (housed at the Louvre Museum, Paris, France) from the 22nd Egyptian Dynasty (943-716 BCE) (Source:

The Egyptian Trinity (right to left): Goddess Isis, Osiris (Isis’ husband) and their son Horus, statuette (housed at the Louvre Museum, Paris, France) from the 22nd Egyptian Dynasty (943-716 BCE) (Source:  Painting by a contemporary American artist Minerva Teichert showing the Jews celebrating the arrival of Cyrus the Great (r. 549–530 BCE) who liberates them for the return to Jerusalem. When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he ordered the sacred religious objects of the Jerusalem Temple to be restored to their rightful owners, the Jews.

Painting by a contemporary American artist Minerva Teichert showing the Jews celebrating the arrival of Cyrus the Great (r. 549–530 BCE) who liberates them for the return to Jerusalem. When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he ordered the sacred religious objects of the Jerusalem Temple to be restored to their rightful owners, the Jews.

Unknown 8,000 year-old ancient goddess from Anatolia from the ancient site of Catal Hoyuk, modern Turkey (Source:

Unknown 8,000 year-old ancient goddess from Anatolia from the ancient site of Catal Hoyuk, modern Turkey (Source:

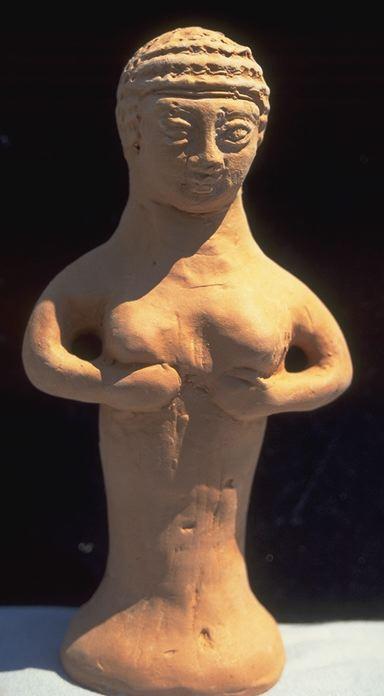

A terracotta figurine of Asherah housed at the National Maritime Museum of Israel in Haifa (Source:

A terracotta figurine of Asherah housed at the National Maritime Museum of Israel in Haifa (Source:

Clay figurine of an ancient Mother Goddess of the Yarmukian Culture of the Neolithic era (Source:

Clay figurine of an ancient Mother Goddess of the Yarmukian Culture of the Neolithic era (Source:  Small clay figurine of an ancient fertility Goddess dated to approximately 7000-7,500 years ago (Source:

Small clay figurine of an ancient fertility Goddess dated to approximately 7000-7,500 years ago (Source:

A traditional portrayal of Ezekiel’s vision (Biblical book of Ezekiel, chapter 1) of the cherubim and chariot (Source:

A traditional portrayal of Ezekiel’s vision (Biblical book of Ezekiel, chapter 1) of the cherubim and chariot (Source: